Stop being customer-driven. Start being customer-centric.

The difference between hearing your customers and truly understanding them.

Imagine you’re steering a boat through fog.

You can feel the hum of the engines, the chatter of the crew, the tension of moving without seeing.

That’s what many companies feel like today: fast, reactive, customer-driven… and directionless.

Being driven means something else is steering.

The illusion of being “customer-driven”

“Customer-driven” sounds virtuous: We listen. We respond. We care.

But in most organizations, it means you’re reacting, not understanding.

At first it feels good. Teams feel useful. Customers seem heard.

But slowly, exhaustion replaces direction.

Customer-driven1 teams:

Chase every request that sounds urgent

Rebuild roadmaps weekly

Confuse motion with progress

They’re like captains who change course every time someone points at a new light on the horizon.

The result: a ship that’s always moving, but rarely arriving.

Being responsive isn’t the same as being relevant.

The customer-centric difference

Customer-centric2 teams still listen, but they listen differently.

They don’t treat feedback as orders, they treat it as data.

They listen for meaning, not volume.

They ask:

What job is the customer trying to get done?

What’s making that job harder than it should be?

How can we solve it once, in a way that helps many others?

Customer-centricity starts where leadership stops reacting and starts asking better questions.

In Lean-Agile3 terms, that means seeing work through the Customer Value Stream4, the sequence of steps where value is actually experienced, not just produced.

Customer-driven teams follow waves.

Customer-centric teams steer by compass.

The request is noise. The job is signal.

Why this matters more than ever

In 2025, products are easy to copy. Understanding isn’t.

Switching costs are near zero and every customer carries a megaphone.

Research from McKinsey, Bain and Forrester shows a consistent pattern:

companies that lead in customer experience tend to grow significantly faster, retain customers longer and convert trust into measurable profitability.

McKinsey notes that CX leaders5 achieve more than double the revenue growth of laggards, while Bain’s work highlights that reducing customer effort is one of the most reliable ways to increase loyalty and reduce churn.

Forrester and others have found that a large share of new software features still fail to deliver measurable value within months of release not because teams don’t move fast enough, but because they solve the wrong problems.

Raw speed isn’t a moat. Clarity is what makes speed compound.

In an age where AI makes imitation effortless, understanding is the only true advantage left.

From noise to signal

Every customer message carries truth hidden in static.

The hard part isn’t hearing customers.

It’s filtering emotion, politics and pressure until you find the pattern underneath

The Noise → The Signal

“Give us more notifications.” → “We’re missing critical changes until it’s too late.”

“Make it more customizable.” →“We can’t align the tool with our specific process without extra work.”

“We need a bigger dashboard on the shop floor.” → “Operators can’t immediately see when performance drops.”

“Add AI assistant” → “We spend hours hunting for answers.”

“Add live chat” → “We’re losing customers during waiting time.”

“More dashboards” → “We don’t trust what we see.”

Customer-driven teams log the noise.

Customer-centric teams decode6 the signal.

They translate symptoms into causes and causes into design decisions.

Clarity never shouts. You have to listen differently to hear it.

In agile systems, this translation happens inside the Continuous Exploration7 cycle, where teams connect market signals with real-world observation before committing code or capacity.

The NASA pencil story: A lesson in signal over noise

One of the most famous examples of confusing noise with signal comes from the early days of the Space Race.

When NASA faced the problem of how astronauts could write in zero gravity, engineers began developing a high-tech “space pen”, pressurized ink cartridges, special materials and millions in R&D investment.

Meanwhile, the Soviet cosmonauts simply used a pencil.

The story (even if partly myth8) illustrates a deeper truth: when you mistake the symptom for the job, you overengineer the solution.

NASA’s “noise” was “We need to design a pen that works in space.”

The real “signal” was “We need a way for astronauts to record information in zero gravity.”

That single shift in framing is the essence of customer centricity.

Being customer-driven would mean building the pen.

Being customer-centric means asking why the pen is needed in the first place.

Solution pollution: when activity replaces understanding

Every organization suffers at some point from solution pollution, the buildup of ideas, features and initiatives launched before the problem is fully understood.

It feels productive: teams are shipping, backlogs are moving, customers are getting “something.”

But like environmental waste, every unvalidated solution leaves residue: complexity, confusion and cost.

Solution pollution happens when listening turns into compliance instead of curiosity.

You collect symptoms, not signals. You fill roadmaps, not gaps in understanding.

The antidote isn’t more prioritization, it’s better diagnosis.

Customer-centric teams clean the ecosystem by slowing down long enough to ask:

“Is this a real need or just a reaction?”

Because every feature built on noise adds friction to the system and clarity always starts with subtraction.

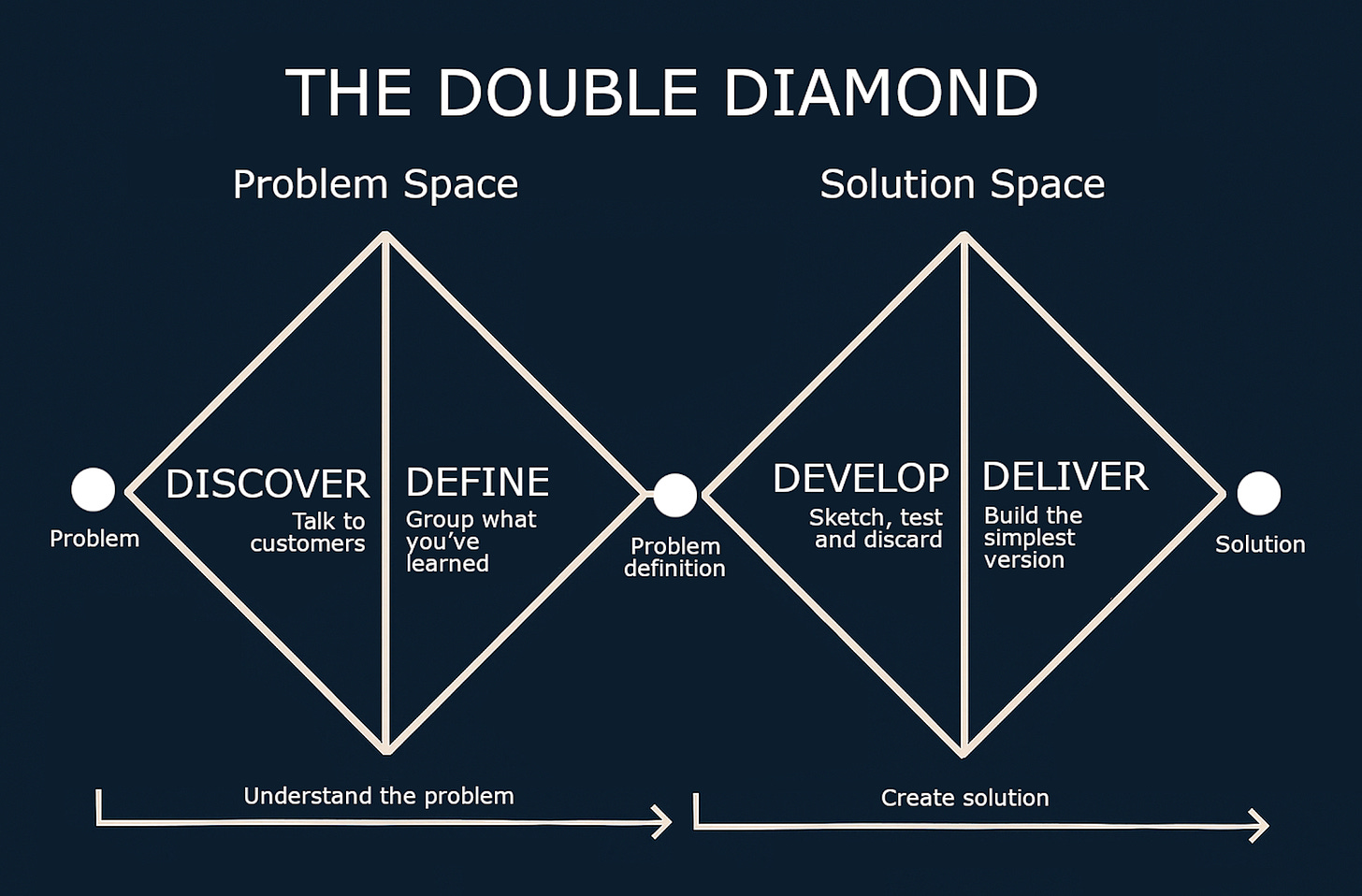

The Double Diamond: a compass for better decisions

The Double Diamond9, created by the UK Design Council, isn’t just a design model.

It’s a rhythm for making better decisions by separating understanding from solving.

Most teams collapse those two moments into one:

They hear a problem and immediately start building.

The Double Diamond forces a pause. It asks you to explore before you decide.

Problem Space

Discover: look wider before you narrow down

Talk to customers. Observe real behavior. Collect raw evidence, not opinions.

The goal isn’t to confirm what you think you know, it’s to find patterns.

Ask: Where are people struggling, improvising or compensating?

Define: frame the real problem

Group what you’ve learned.

Then write one clear statement that captures the essence of it.

For example: “Finance teams don’t need faster exports, they need fewer manual steps.”

This becomes your North Star for the next phase.

Solution Space

Develop: explore multiple ways to solve it

Don’t jump to your favorite idea.

Sketch, test and discard.

Look for approaches that solve the job, not just add a feature.

Invite cross-functional teams (engineering, support, customer success) to test small.

Deliver: make it real and measure the outcome

Build the simplest version that proves the solution works.

Then measure whether customer behavior changes in the intended direction:

shorter cycle times, fewer workarounds, higher confidence.

Iterate around evidence, not internal opinions.

Example: One SaaS team used this rhythm to clean up a chaotic backlog10.

Two weeks in Discover revealed that 80 % of requests traced back to four core jobs.

By Define, they had a focused roadmap and calmer planning sessions.

The Double Diamond isn’t about slowing down.

It’s about thinking in focus before acting in force.

Skip the first diamond and you’ll move quickly in the wrong direction.

Use both and you’ll finally steer with intent.

The Kano Model: not every request deserves a feature

Understanding customer needs isn’t just about collecting requests, it’s about recognizing which ones actually drive satisfaction.

That’s where the Kano Model helps: it separates what customers say they want from what truly delights or frustrates them.

Kano identifies five categories of customer expectations:

Basic Needs (Must-be):

The essentials customers rarely mention until they fail.

When missing, they cause frustration. When present, they’re taken for granted.

Example: data security, system reliability, invoice accuracy.Performance Needs (More-is-better):

Directly correlated with satisfaction: the faster, easier or cheaper something gets, the happier the customer.

Example: page load time, processing speed, time-to-close.Delighters (Exciters):

Unexpected features that spark loyalty and differentiation, until they become expected tomorrow.

Example: automatic anomaly detection, predictive alerts, zero-click setup.Indifferent Needs:

Elements that neither add nor reduce satisfaction. Customers simply don’t care.

Example: cosmetic interface tweaks that don’t change usability or redundant customization options.Reverse Needs:

Features that actually reduce satisfaction when added or overemphasized.

Example: overly complex automation, excessive notifications or mandatory personalization that feels intrusive.

Customer-driven teams often chase delighters reactively, trying to surprise, impress or please every request that sounds exciting.

Customer-centric teams use frameworks like Kano to distinguish between hygiene, performance and true innovation, ensuring that effort aligns with lasting value.

The goal isn’t to do everything customers ask for.

It’s to understand which needs sustain trust and which truly create delight.

A moment of realization

Picture a product team in a room covered with sticky notes.

Requests from customers, partners and sales everywhere.

The CEO looks at the board, then at the team.

A minute ago the room was buzzing. Now? Quiet!

He finally says:

“We’re making customers happy. But are we making them successful?”

That was the turning point.

They stopped chasing noise and started mapping customer jobs-to-be-done11.

Within months, the backlog was half the size and customer satisfaction went up.

They didn’t have to build more. They had to build right.

A real-world example

A mid-market fintech kept hearing the same request:

“Add more export formats.”

They almost shipped it until a customer success lead asked a simple question:

“Why do you need them?”

After 12 short interviews, the pattern was clear:

“We just want to close the books without late nights.”

Instead of adding export formats, the team built auto-reconciliation with anomaly detection.

Support tickets dropped 40 %, month-end close became 30 % faster and renewal rates rose by 12 points.

When teams start solving for progress instead of preference, they stop wasting effort and customers notice.

The economics of understanding

Understanding feels slow, but it’s the fastest path to results.

A wrong feature burns engineering time, marketing money and credibility all at once.

It also trains your teams to confuse urgency with importance.

Gartner estimates that 35% of development resources in B2B SaaS go to unused features.

That’s what empathy12 without clarity costs.

Solving the right problem once is cheaper than solving the wrong one three times.

Empathy isn’t soft. It’s capital discipline disguised as care.

The cultural resistance

Every company claims to value understanding until it slows delivery.

The usual blockers:

Hero culture15: speed gets applause, insight doesn’t.

Political safety: saying “yes” feels easier than “not now.”

How to fix it:

Redefine success: learning before launching.

Reward insight, not just output.

Let leaders model patience.

A CEO who says “Let’s listen first” gives everyone permission to think.

Lean-Agile leadership calls this “Go See” or “Gemba”16 spending time where value is created and experienced, not just reported.

It’s empathy by design, not by chance.

But culture changes the same way trust does: through a thousand small, consistent signals.

From principle to practice: how to apply this

Big shifts rarely start with big programs.

They start with a single team asking a better question.

Customer-centricity isn’t a mindset you declare.

It’s a rhythm you practice.

Here are simple ways to start changing direction today.

Start every project with a “Problem Frame.”

Before you design or code anything, answer three questions:What customer job does this support?

What friction are we solving?

How will we know it worked?

→ Forces clarity before motion.

Run “Noise vs. Signal17” sessions.

Once a month, take all customer requests.

Write the literal words on one side (“Noise”), the real goal on the other (“Signal”).

Patterns will jump out. Teams will start listening differently.Create a simple “Customer Compass18” board.

Three columns on a wall or digital board:Top 3 customer jobs

Top 3 pain points

Top 3 experiments in progress

When decisions get noisy, look up. That’s your compass.

Link metrics to real outcomes.

Add to your dashboards:Ask better questions in meetings.

Replace “When can we ship?” with:“How do we know this solves the right problem?”

“What behavior should change if we’re right?”

“What evidence do we already have?”

Celebrate insight, not just delivery.

At your next all-hands, don’t just celebrate launches.

Celebrate learning moments.

“We discovered the real friction behind feature X and it changed our roadmap.”

Culture changes when curiosity gets applause.

That’s how momentum turns into direction.

Reflection for leaders

If you lead a team, ask yourself:

Do we know our customers’ top three outcomes?

Would our roadmap make sense to them or only to us?

When did we last say “no” for a good reason?

Are we steering by compass or chasing every wave?

These aren’t rhetorical questions.

They’re the start of a new kind of conversation inside your company.

If they feel uncomfortable, good.

That’s the beginning of clarity.

A note on nuance

While the distinction between customer-driven and customer-centric clarifies two opposing reflexes, the real world is rarely that binary. Mature organizations learn to balance both forces: responsiveness keeps them humble and fast, centricity keeps them coherent and focused. Listening without discipline creates noise, but discipline without listening breeds detachment. In Lean-Agile environments, these tensions play out daily, between exploration and delivery, learning and commitment, autonomy and alignment.

True customer centricity is not the absence of reactivity, it is the ability to react with intent. Leading organizations like Toyota, Amazon or Spotify illustrate this balance daily, they use continuous feedback loops to sense real-time shifts, yet steer through enduring customer principles that act as their compass. This integration happens where teams align discovery and delivery rhythms using customer outcomes, not opinions, as their shared north star.

In practice, this means designing systems that make doing the right thing (not the loud thing) the path of least resistance. The challenge isn’t choosing between being driven or centric, it’s learning to integrate both into one rhythm that adapts without losing direction.

Final thoughts

Customer-driven teams move fast, often in circles.

Customer-centric teams move deliberately and arrive.

The first listen to everything.

The second understand something.

The first react.

The second navigate.

Because the goal isn’t to move faster.

It’s to move truer.

Customer-centricity isn’t about saying yes more often.

It’s about seeing more clearly and steering with intent.

Because when you steer with intent, customers feel it and that’s what makes trust scale.

In Lean-Agile systems, customer centricity isn’t a department, it’s a decentralized reflex.

Everyone, from engineers to executives, learns to sense where value flows and where it stalls.

Further reading

Harvard Business Review: “Know Your Customers’ Jobs to Be Done”

UK Design Council: “What Is the Double Diamond?”

Harvard Business Review: “The Value of Customer Experience, Quantified”

McKinsey & Company: “Experience-Led Growth”

Lance B. Coleman: The Customer-Driven Organization: Employing the Kano Model

Glossary

Customer-Driven: Organizations that react to customer requests without distinguishing urgency from importance. Activity replaces direction.

Customer-Centric: A disciplined approach to understanding customer needs and aligning decisions around long-term value rather than short-term demand.

Lean-Agile Leadership: A leadership style emphasizing trust, learning and decentralized decision-making over command and control. Decentralized Decision-Making means empowering those closest to the work to make informed decisions quickly.

Customer Value Stream: The sequence of steps through which a customer actually experiences value. It is used to design around outcomes, not processes.

CX Leader (Customer Experience Leader): Organizations that outperform peers by consistently delivering superior customer experiences across the entire journey.

Decoding Requests: Translating what customers ask for into what they actually need to achieve.

Continuous Exploration (CE): Ongoing discovery of customer needs and market shifts before committing development resources.

Fact check of the NASA Pencil Story: Both NASA and the Soviet space program initially used pencils, but graphite dust was a fire and equipment hazard inside oxygen-rich capsules. The “space pen” was later invented privately by Paul C. Fisher in 1965 at his own expense (≈ $1 million R&D). NASA purchased the pens for $2.39 each after testing and the Soviets soon did the same. The “NASA spent millions” part of the story is a myth, yet the example remains a powerful metaphor for solving the right problem instead of the requested one.

Double Diamond: UK Design Council model dividing problem-solving into four phases: Discover, Define, Develop and Deliver to separate learning from building.

Backlog: A prioritized list of ideas or features waiting for implementation. It becomes meaningful only when tied to measurable value.

Jobs-to-Be-Done (JTBD): A framework for seeing products as tools customers “hire” to accomplish a goal or solve a problem.

Empathy as Capital Discipline: Treating empathy not as sentiment but as a way to avoid wasted investment through deeper understanding.

KPI Addiction: Obsessive focus on performance metrics at the expense of meaningful outcomes.

Outcomes vs. Outputs: Outputs are deliverables. Outcomes are the actual results or changes they create for customers.

Hero Culture: A behavior pattern where individuals gain status for reacting fast, even when the action lacks alignment or clarity.

Gemba / Go See: Lean leadership practice of visiting the place where value is created to observe reality directly.

Noise vs. Signal: The distinction between surface-level customer requests (noise) and the underlying need or intent (signal).

Compass Thinking: Making strategic decisions guided by purpose and direction, not daily turbulence or pressure.

Time-to-Value (TtV): The time between a customer’s first use and the moment they realize tangible benefit.

Customer Effort Score (CES): Metric measuring how easy it is for a customer to complete a task or resolve an issue.

Seriously, this article comes at the perfect time, because I was just thinking what if all that 'chasing every request' just makes us feel busy, like we were shipping features, but without actually solving the underlying 'job to be done' for the customer.