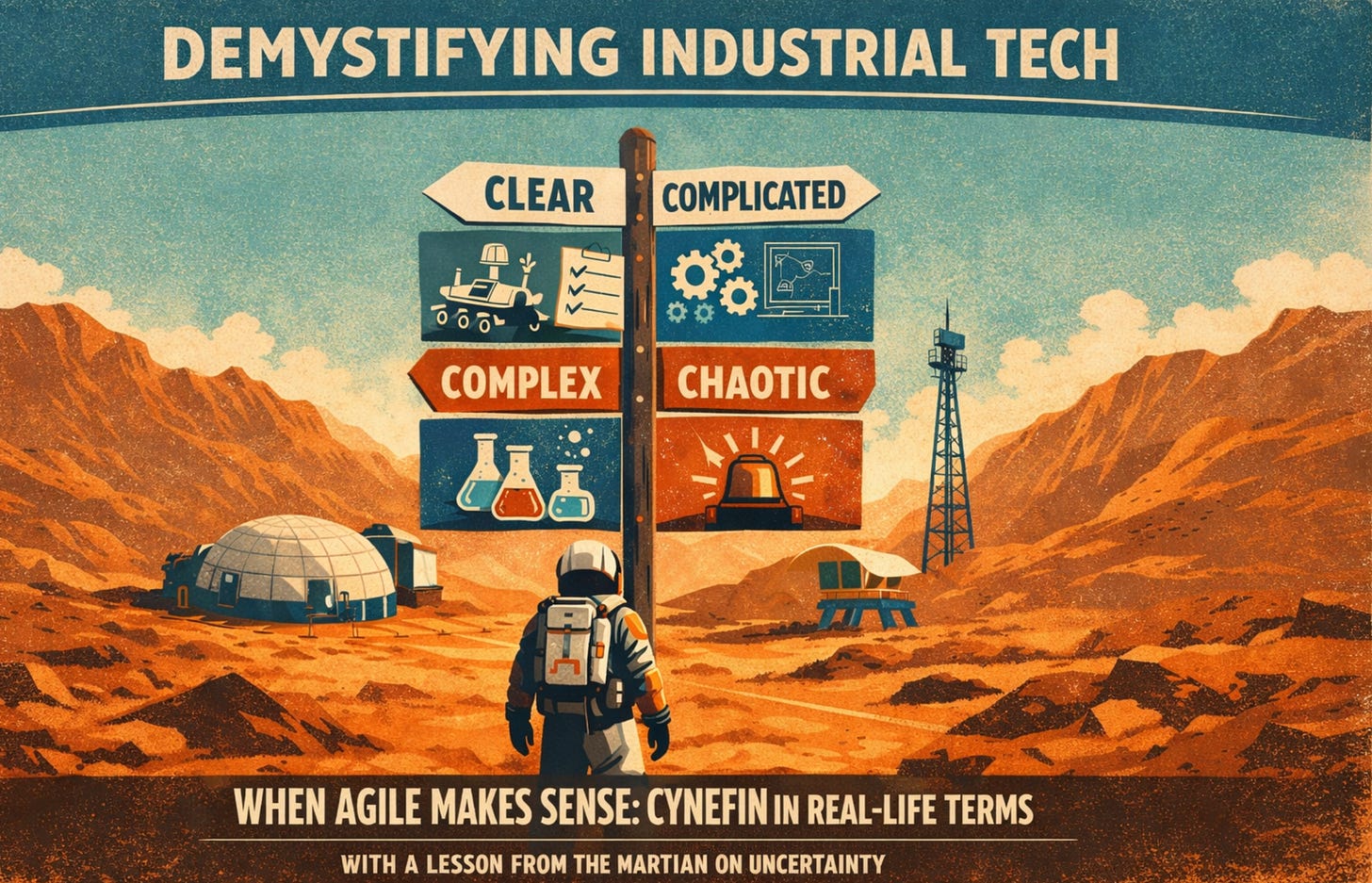

When Agile makes sense: Cynefin in real-life terms

With a lesson from The Martian on uncertainty

Most teams don’t fail because they chose the “wrong agile framework”. They fail because they treat different kinds of work as if they were the same kind of work.

Cynefin1 gives you a simple way to name what you’re dealing with, so you can protect agility where it creates real value and avoid wasting it where execution is the real job.

If you’ve seen The Martian, you’ve already watched a Cynefin story.

Mark Watney survives on Mars by switching between different modes of action, depending on the kind of situation he’s in:

When things are clear and repeatable, he follows procedures and executes carefully. No improvisation. Just discipline.

When problems are hard but knowable, he relies on engineering judgment and careful analysis (sometimes with help from experts back on Earth).

When things are uncertain, he runs small experiments, observes what happens and adapts based on what he learns.

And when things suddenly go sideways, the first priority is stabilizing the situation, not debating process or running experiments.

That’s Cynefin in a nutshell: match your approach to the nature of the problem.

Most failures happen when people argue about what to do before agreeing on what kind of situation they’re actually in.

Most organizations try to run one mode for all four situations and that’s how agile gets blamed for problems it was never meant to solve.

Agile has become widely adopted and that’s a good thing.

It pulled product work away from “big plans, late surprises” and back toward users, feedback and learning. Many teams ship better software (and even better hardware) because of it.

The problem isn’t agile.

The problem is when “go agile” becomes the default answer, even when the work is mostly known and the real need is reliable execution.

That’s how you end up with agile fatigue: more meetings, more tickets, more ceremonies… and somehow less clarity.

The Cynefin framework helps you avoid that trap. It doesn’t replace agile. It helps you aim agile and it gives you permission to use other approaches when learning isn’t the bottleneck.

Before you argue about Scrum vs. Kanban vs. “our hybrid”, agree on what you’re dealing with: executing something known, designing something difficult, exploring something uncertain or stabilizing a mess.

This article is for product and engineering leaders working on:

standard products and platforms

customer-specific development

software and hardware

The goal: after reading, you should be able to use Cynefin in real decisions, not just recognize the diagram.

Cynefin without the diagram

Cynefin distinguishes four domains based on how clear the relationship between cause and effect is.

Clear – cause and effect are obvious

Complicated – cause and effect exist, but require expertise

Complex – cause and effect only become clear after experimentation

Chaotic – there is no stable cause-effect relationship yet

The core idea is simple:

Different kinds of problems require different ways of deciding and managing.

Where organizations get hurt is when they apply the same logic everywhere, usually because it feels comforting.

The Lego metaphor (one toy, four worlds)

Lego2 is useful here because it strips away politics. It’s just a thing you’re trying to build.

1) Clear: Build the model from the box

You have instructions. If you follow them, you get the Millennium Falcon. If you don’t, you get a sad gray blob.

If something goes wrong, it’s usually execution, not discovery.

Typical signals:

there is a known procedure

quality can be checked against a specification

mistakes are repeatable

Best approach:

Process, checklists, automation.

Agile value: limited here. Agile principles still help (visibility, collaboration), but discovery is unnecessary.

If you remember one thing: Standardize it and remove avoidable variation.

Mini-example (software): rolling out a known configuration change across environments.

Mini-example (hardware): assembling a proven module where tolerances and test steps are fixed.

Common mistake: treating routine delivery like a research problem. People debate “how” when the answer is “follow the steps”.

2) Complicated: Design a custom Lego machine

Now you want a Lego crane that lifts a specific load without tipping.

There’s no manual, but experts can design it. Analysis, simulation and review reduce risk.

Typical signals:

experts disagree, but one can be right

trade-offs can be explained

analysis improves outcomes

Best approach:

Expert design, reviews, staged decisions.

Agile value: supportive. Agile helps with coordination and transparency, while expert design remains central.

If you remember one thing: Let experts design and make decisions explicit.

Mini-example (software): designing a permission model that won’t paint you into a corner.

Mini-example (hardware): thermal design for a device that must survive real-world heat.

Common mistake: confusing “hard” with “uncertain”. Complicated work can be tough and still be predictable with expertise.

3) Complex: Create a new Lego play experience

Now you’re not building a model. You’re trying to create fun.

You want kids to love it. You don’t know what will work until you try and kids won’t behave the way your slide deck expects.

Understanding emerges through experimentation.

Typical signals:

users can’t fully articulate needs

behavior surprises you

early assumptions keep changing

Best approach:

Experiments, feedback, short learning cycles.

This is where agile shows its full strength.

If you remember one thing: Run small, safe-to-fail experiments to learn what’s true.

Mini-example (software): onboarding. Everyone has opinions. Only users’ behavior tells you what’s actually confusing.

Mini-example (hardware): ergonomics. A button location that looks perfect in CAD can be awkward in real hands.

Common mistake: asking for “final requirements” too early. In complex work, requirements are often the output of learning, not the input.

4) Chaotic: Lego explosion on the floor

Everything is breaking down. Pieces everywhere. Someone’s panicking. Maybe you are.

In chaos, you don’t run a workshop. You stabilize.

Best approach:

Decisive action, command, stabilization, then reflection.

Agile value: temporarily paused during chaos. Once stability is restored, agile practices help with learning and prevention.

If you remember one thing: Stabilize first, then learn.

Mini-example (software): a production outage with unknown cause.

Mini-example (hardware): a safety issue discovered in the field.

Common mistake: trying to “process” your way out of chaos while damage is still happening.

The domain most teams live in: Disorder

Cynefin is often shown with a fifth context in the center: disorder (sometimes called confusion).

That’s when people assume different domains at the same time:

Sales treats the work as clear (“just deliver what we promised”)

Engineering treats it as complicated (“we need design time, this has risks”)

Product treats it as complex (“we need experiments, we don’t know what works yet”)

If you’ve ever sat in a meeting where everyone talks past each other, this is usually why.

What disorder looks like in real life

A customer asks for “a dashboard that improves decision-making”.

Sales hears: “build dashboard A by date B”.

Engineering hears: “unclear scope + integration risks”.

Product hears: “we don’t know which decisions, for whom and why”.

Everyone is being reasonable (in their own domain).

Cynefin’s first practical use: force alignment on what kind of problem this is before discussing scope, estimates or commitments.

A simple question that resets the room:

“Are we executing something known, designing something hard-but-knowable or learning what ‘good’ even means?”

Why organizations misclassify problems

Misclassification is rarely a knowledge issue. It’s structural.

Common drivers:

Planning pressure: leaders want predictability, so complexity gets simplified away

Sales incentives: uncertainty doesn’t sell well

Fear of accountability: calling work “complex” can hide indecision, calling it “clear” can hide risk

Tool bias: teams squeeze problems into the method they already run

Cynefin doesn’t remove these forces, but it makes them visible. And visibility is the first step to better decisions.

Leadership looks different in each domain

This is one of the most overlooked parts of Cynefin.

Domain Leadership Focus

------------------------------------------------------------

Clear Enforce standards, reduce variation

Complicated Enable experts, make informed decisions

Complex Set direction, protect learning, remove fear

Chaotic Act decisively, restore orderWhat makes this practical is the “feel” of getting it wrong:

Complex led like clear → people hide bad news, learning slows down, you get polished updates and ugly surprises.

Clear led like complex → endless discussion about obvious work and teams lose momentum.

Complicated led like complex → decisions get postponed in the name of iteration and technical debt quietly piles up.

A quick gut-check for leaders:

“Do I need more control here… or more truth?”

In complex work, you usually need more truth.

What to measure (this is where teams accidentally break agile)

One reason agile turns into theater is that teams use the wrong success metrics.

Different domains require different signals.

Clear: throughput, error rates, compliance

Complicated: decision quality, rework, technical risk reduction

Complex: learning velocity, hypothesis changes, decision improvements

Chaotic: time to stabilization, damage contained

The important warning

Don’t mix these casually.

If you measure delivery output in complex discovery work, you’ll optimize for speed over learning.

That’s how you get:

“We shipped something!” (nobody uses it)

“We hit the sprint goal!” (the goal wasn’t the right goal)

“Velocity went up!” (and so did the feature graveyard)

A healthier question in complex work:

“What did we learn that changed a decision”?

If the answer is “nothing”, you’re either not in complex work or you’re not doing the learning part.

Domains are not static (and that matters more than people think)

Good product work intentionally moves problems between domains.

A healthy pattern:

start complex (discover value)

move to complicated (design solutions)

end clear (execute reliably)

Two failure modes show up all the time:

Failure mode 1: Staying complex forever

Teams keep “experimenting” because converging means making hard decisions.

You’ll hear:

“We’re still validating”.

“We need one more test”.

Sometimes that’s true. Often it’s fear.

Failure mode 2: Forcing clarity too early

Leaders demand firm plans when reality is still uncertain.

That doesn’t remove uncertainty. It just buries it.

A useful product leadership move is to say:

“This is complex for now. Our job is to make it complicated, then clear”.

That’s not anti-agile. That’s agile done with purpose.

Applying Cynefin to Standard Product Development

Software Products

Early stages are mostly complex: value, behavior, adoption.

Later stages mix domains:

discovery remains complex (new segments, pricing, positioning)

architecture and scaling are complicated

operations and rollout become clear

Practical move: separate learning work from execution work.

A simple way:

a learning lane (experiments, prototypes, discovery)

a delivery lane (engineering execution)

If you blend them, both suffer.

Hardware Products

Hardware is often misunderstood as “non-agile”.

Reality:

discovery and desirability are complex

engineering trade-offs are complicated

manufacturing execution is clear

Agility works best at interfaces:

hardware–software integration

user interaction

real-world usage (where assumptions go to die)

If you want one rule of thumb:

Be agile where feedback is cheap. Be structured where changes are expensive.

Applying Cynefin to Customer-Specific Development

Customer work is where misclassification is most expensive, because promises get made early.

Truly complex customer work

Complex when:

the customer problem is unclear

success criteria evolve

the solution must be discovered together

What to do:

explicitly define a discovery phase

time-box experiments

agree on decision points (not feature lists)

Human wording that works:

“We can’t responsibly commit to the full solution yet. We can commit to reducing uncertainty fast and making better decisions”.

Complicated (but often mislabelled as complex)

Many customer projects are difficult but predictable.

They need:

upfront clarification

expert design

structured delivery

Calling this agile doesn’t make it adaptive, it just avoids decisions.

A concrete example

Customer: “We need integration with our ERP”.

If it’s a known interface and known data mapping → complicated (expert delivery)

If the customer doesn’t know which processes matter or success is “less manual work somehow” → complex (co-discovery)

Same sentence. Completely different domain.

One more quick example:

Customer: “We need a dashboard that improves decision-making”.

If the decisions, users and success signals are clear → complicated/clear (deliver to spec).

If nobody can define what “better decisions” means yet → complex (discover outcomes first).

The Highest-ROI move: split work by domain

Most real projects contain all domains.

Instead of choosing one method, split the work:

Discovery (complex): experiments and learning goals

Design (complicated): expert decisions and reviews

Execution (clear): process and automation

This single step often removes months of friction because you stop treating everything like it has the same uncertainty level.

A 60-Minute Cynefin workshop you can actually run

This is simple, but it won’t be perfectly comfortable. That’s the point.

List major work items (10 min)

not tasks, real work items (“new onboarding”, “customer integration”, “new device form factor”)

Map each to a domain and justify placement (20 min)

require one sentence: “We think this is complex because…”

Agree on the approach per domain (15 min)

process vs. expertise vs. experiments vs. stabilization

Define success signals per domain (15 min)

especially for complex: “what would we learn that changes our decision?”

If people argue about classification, don’t shut it down. That argument is the value. It reveals disorder.

Common failure modes Cynefin helps prevent

Agile unintentionally used to postpone decisions

Detailed plans in complex uncertainty

Treating everything as urgent chaos

Measuring output where learning is needed

Agile doesn’t remove complexity, but Cynefin helps ensure agility is applied where it creates real value.

Getting started (without overthinking it)

Add one slide to project kickoffs: Which domain are we in?

Change language: delivery plan vs. learning plan

Promise learning where certainty is impossible

Adjust metrics to fit the domain

Re-classify on a cadence (monthly is a good start) and immediately after any major surprise

Final thoughts

Cynefin doesn’t tell you what to do.

It helps you stop doing the wrong thing for the wrong kind of problem.

Used well, it gives leaders permission to:

be predictable where they should

be exploratory where they must

and be decisive when it matters most

And sometimes, the most agile and professional statement in the room is:

“This isn’t complex. Let’s not pretend it is”.

That clarity alone can save months.

Further Reading

Dave Snowden: the Cynefin framework (articles, talks and the original framing)

Harvard Business Review: A Leader’s Framework for Decision Making (David J. Snowden & Mary E. Boone)

Teresa Torres: Continuous Discovery Habits

Marty Cagan: INSPIRED (product discovery) and EMPOWERED (product leadership)

Eric Ries: The Lean Startup

Cynefin® is a registered trademark of its respective owner. This article is independent commentary and not affiliated with or endorsed by The Cynefin Company.

LEGO® is a registered trademark of the LEGO Group, which does not sponsor, authorize, or endorse this article. LEGO is used here purely as a familiar real-world analogy.

That's very good advice. I was not aware of Cynefin, but I will check it out.

Thank you for sharing these insights. I've been part of many agile vs waterfall discussions as option A option B option C hybrid. I really like the way you lead a rubric on how to select a clear path forward.