The Complexity Brake: When “Let’s think this through” really means “Let’s not do this”

A leadership field guide to spotting fake complexity, cutting through it and shipping something real

A lot of work doesn’t die because it’s a bad idea. It dies because someone quietly turns it into a spreadsheet-sized problem, right when it’s time to move.

Not with sabotage. Not with drama.

With a calm, reasonable-sounding “Yes, but…” that keeps growing until everyone eventually shrugs and says: “Maybe we should park this.”

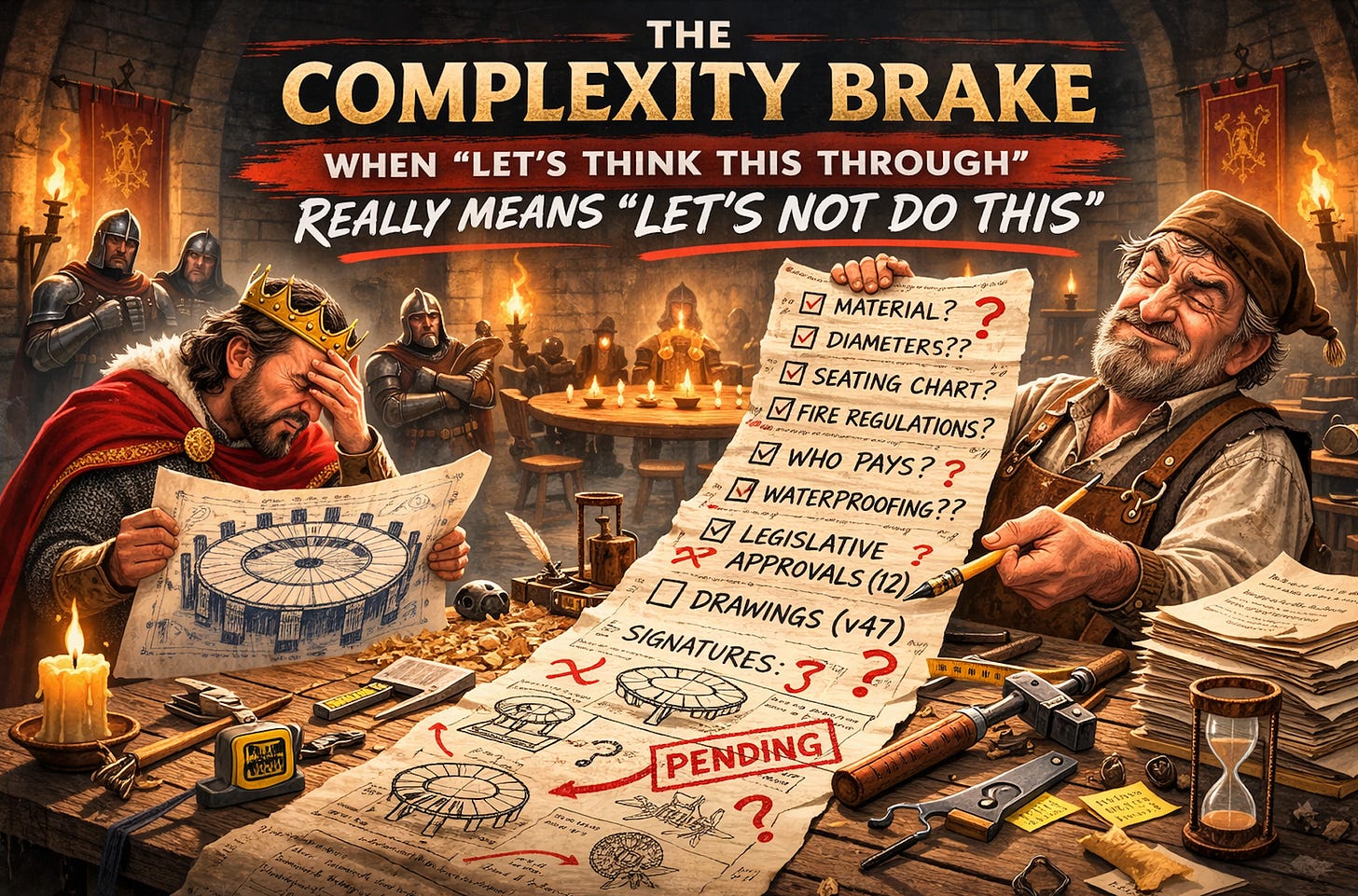

That pattern has a name: avoidance through overcomplication. I call it the complexity brake, because it doesn’t crash the car. It just makes sure it never leaves the driveway.

Before we get into timeboxes and templates, let me show you what this looks like in the wild. There’s a short film that captures the entire pattern in one painfully funny scene.

A real joke from the Dark Ages (and why it hits so close to home)

Dark Ages (Finstere Zeiten) is a German short film from Badesalz1, a cult-famous comedy act from the German state of Hesse, that opens like it wants to be the most serious medieval epic ever made.

You get the full package: chaos, combat, torches, metal, mud, big dramatic energy. It sets the tone as “dark times”, the kind of story where you assume the main threat will be war, betrayal or some enemy at the gates.

And then the film pulls the rug.

Because the real threat isn’t an invading army.

It’s… a requirements discussion.

After the battle mood settles, King Arthur steps into the “new era” role. He’s got the big leadership speech, the big vision, the “we’re done with this nonsense and we’re building something better” posture. He wants to found the Round Table, a symbol of a different kind of order.

So far, this is every leadership offsite you’ve ever attended, just with more chainmail.

Then Arthur does the most normal thing a leader can do: he calls in someone to build the thing.

Enter the carpenter. A practical guy. Grounded. Confident. He’s not impressed by symbolism. He’s impressed by wood, measurements and what can go wrong if you do something “wrong.”

Arthur says he wants a round table for 25 people.

The carpenter does not say “No.”

He says “Sure.”

And then he starts doing what some people do incredibly well: he turns a simple “yes” into a slow-motion shutdown without ever openly opposing the idea.

It’s not one objection. It’s a cascade (in a thick Hessian dialect). A drip-feed of “practical” concerns that are individually reasonable and collectively lethal.

Arthur keeps trying to speak at the level of vision: what it means, what it represents, why it matters.

The carpenter keeps dragging the conversation down into gritty, exhausting detail, so relentlessly that the whole project starts to feel like a burden rather than an opportunity.

That’s where the comedy lives: the collision between myth and minutiae.

Arthur is trying to build a new society.

The carpenter is trying to “clarify the scope.”

And the carpenter’s superpower is that he makes the path forward feel endless. Each time Arthur tries to wrap it up, there’s another “one more thing,” another edge case, another condition that “we really should sort out first.”

You can watch Arthur’s energy drain. Not because he’s been defeated by a better argument (there is no decisive argument). He just gets worn down by the sheer weight of the conversation.

That’s the punchline: the king who survived war can’t survive an endless pre-flight checklist.

Eventually Arthur does what people do in real companies all the time: he disengages. He backs off. Not because it’s impossible, but because it’s become emotionally expensive. The table doesn’t happen. Not because the idea is bad, but because it’s been talked to death.

And then the film lands the extra little twist that turns it from “funny scene” into “ouch, that’s a pattern.”

A second legendary customer shows up: Robin Hood, with his own plan. And the carpenter runs the exact same routine again (immediately turning the next big idea into a swamp of “but what about…” until that customer also basically flees).

Same carpenter. Different initiative. Same outcome.

That’s the whole lesson in one medieval room:

Nobody says “no.”

They just make the “yes” so exhausting that the other side quits.

That’s the complexity brake in its purest form. Now let’s translate that into what it costs in a modern organization and what leaders can do about it.

Why leaders should care (this is not just an “efficiency” thing)

The complexity brake is expensive in a very specific way: it creates waiting.

If you’ve read my DIT piece about waiting time, you already know the punchline: customers don’t experience your internal effort. They experience how long it takes to get something real. Internally, teams experience the same thing (work sitting idle between steps, especially between decisions).

Over time, that “idle time” turns into outcomes you can feel:

decisions get slower, so learning gets slower

opportunities pass while you “align”

teams get cynical (“we don’t do things here”)

strong people leave because they’re tired of pushing air around

What this pattern is (and what it isn’t)

At its core, the complexity brake is simple: someone adds enough conditions, approvals, edge cases and “one more analyses” that action becomes socially impossible.

But it’s important to say what it isn’t, because otherwise the wrong people will use this post as a weapon.

It isn’t an argument for recklessness. It isn’t “move fast and break things.” It isn’t “stop thinking.”

Real diligence reduces uncertainty and creates a path forward.

Avoidance increases uncertainty and delays commitment.

A quick reality check, so nobody hears “speed at all costs”:

If you’re changing a safety interlock, signing an irreversible contract or doing something that could plausibly harm customers, patients or workers. You should be methodical. That’s adult supervision.

But if you’re debating a pilot, a draft or a two-week test and the room keeps inventing reasons to postpone… that’s usually not safety. That’s the brake pedal.

How it shows up in real life

You usually spot the complexity brake through timing.

Everything looks fine… until it’s time to start. Then suddenly the initiative becomes “more complex than we thought.”

It tends to show up in a handful of costumes:

Kickoff inflation. Two days before the start, new requirements appear. Not improvements. Gatekeepers.

Approval laundering. “I’m not against it, but Legal has to sign off.” “Security will never allow this.” “The CFO won’t like it.”

Notice what’s missing: someone actually talking to Legal, Security or the CFO (with a deadline).

Meeting motion without decisions. You get open questions, action items and follow-ups… and somehow no owner, no decision, no date. (If you’ve read my Meeting-Tourism piece, you’ve seen this pattern.)

Bikeshedding. The group debates easy details (wording, formatting, tooling) because the real decision is uncomfortable.

Risk as a veto. Risks are raised like stop signs, but nobody proposes a mitigation or a test.

Why people do it (and why it’s not always malicious)

Sometimes this is just human self-protection: fear of being judged, fear of being “the person who was wrong,” fear of conflict, fear of being evaluated.

Sometimes it’s overwhelm: complexity becomes a shield when someone feels out of their depth.

And sometimes it’s the system you built around them: unclear priorities, unclear decision rights, blame culture, chronic overload. In those environments, “not deciding” becomes a rational move.

This is where psychological safety matters, not as a soft topic, but because it determines whether people can say, “I’m not sure” or “Let’s test it small” without getting punished for it.

The intent question: self-protection vs. strategic stalling

Most leaders make the same mistake here: they treat every brake pedal like it’s the same.

Sometimes it’s unintentional: a smart person trying not to get burned.

Sometimes it’s intentional: complexity used to avoid ownership, avoid conflict or keep control.

You don’t need mind-reading. You need pattern-reading:

Do they become “thorough” only when the work would put them on the hook?

Do they slow down projects that threaten their turf, but move fast when it benefits them?

Do they always “need alignment” but never do the aligning?

If it’s intentional, don’t solve it with more process. Solve it like a leadership issue: clarity, expectations, consequences.

When slowing down is actually the right move

Here’s the guardrail that keeps this post from being misused:

Slow down when the decision is truly hard to reverse (major capex, irreversible contract terms) or when safety/regulatory/security risk is real and immediate.

Everything else? Treat it as a two-way door. Try, learn, adjust, roll back. Most organizations waste months treating reversible choices like courtroom cases.

What leaders can do (without turning into the “just do it” cliché)

You don’t fix the complexity brake with pep talks. You fix it by changing what’s allowed in the room.

Start with this rule:

Risk only counts if it comes with a countermeasure.

If someone raises a risk, they also propose a mitigation or a test. If they can’t, it’s not a blocker yet, it’s a worry.

Then add a clock:

Timebox the debate. “We’ll discuss risks for 45 minutes. Then we choose: go, run a small test or kill it.”

Then solve the accountability problem in a healthy way:

Name one owner and protect them. Ownership is coordination, not blame. The owner’s job is to drive the next step and bring learning back. The leader’s job is to prevent ownership from turning into scapegoating.

If you want one sentence that changes the mood instantly, use this:

“If the experiment fails, I’ll own it publicly. You own the learning.”

Finally, enforce meeting hygiene:

Every meeting ends in one of three outcomes: decision, experiment or kill.

No fourth option called “great discussion.”

Two mini-templates your team can actually use

These aren’t fancy. That’s the point.

Template 1: The 2-Week Experiment Card

Hypothesis: We believe that ____ will lead to ____.

Smallest test (2 weeks): We will ____.

Owner: ____.

Success metric: We’ll measure ____.

Stop / pivot rule: If ____ happens, we stop or change approach.

Decision date: ____ (calendar invite sent).

Template 2: Risk → Countermeasure (one line each)

Risk: ____

Impact: ____

Countermeasure / test: ____

Owner + date: ____

If the countermeasure line stays blank, you don’t have a risk management discussion, you have a fear-sharing session.

Phrases that cut through “Yes, but…” without starting a fight

Keep these in your back pocket:

“What’s the smallest testable version we can run in two weeks?”

“Which assumption is blocking us? And how do we test it?”

“Is this reversible? If yes, why aren’t we deciding today?”

“Who owns this and what’s the next step by Friday?”

“If we do nothing for six weeks, what does that cost us?”

“What decision are we avoiding by debating these details?”

A modern version of the Dark Ages scene (you’ve seen this meeting)

Monday. Steering committee. A pilot is ready.

Someone says: “Before we run a pilot, we need an enterprise-wide governance model.” Then: “And a vendor bake-off.” Then: “And a complete data classification effort.” Then: “And training for every site.”

At that point, you’re not hearing diligence. You’re hearing a medieval carpenter building a career out of never cutting wood.

Here’s the clean move:

“What’s the smallest test that produces real evidence in two weeks?”

If nobody can answer, you’ve found the brake pedal.

And if the room suddenly can answer once you ask that question? Great. That means it was never truly complex. It was just emotionally expensive.

Getting Started (without overthinking it)

Pick one stuck initiative this week and run a simple reset:

Name one owner. Write “done” in one paragraph. List the top three risks (each with a mitigation or test). Timebox the debate. End with go/test/kill. If it’s “test,” create the 2-Week Experiment Card and schedule the review immediately.

That’s enough to change momentum without launching a new “program.”

Final Thoughts

Complexity isn’t the enemy. Reality is complex.

The enemy is complexity used as cover to avoid ownership, avoid conflict, avoid being evaluated or avoid the uncomfortable work of choosing.

Your job isn’t to stop questions. Your job is to make sure questions lead somewhere real: a decision, a test or an honest “no.”

And if someone keeps finding reasons not to build the table?

At some point, it’s not about wood. It’s about leadership.

Links (DIT)

Customers don’t experience your effort. They experience waiting. (demystifyingindustrialtech.com)

Escaping the Meeting-Tourism Trap. (demystifyingindustrialtech.com)

Done > Perfect: Why people overdeliver and how leaders can break the cycle. (demystifyingindustrialtech.com)

From “Permit A38” to Progress: cutting bureaucracy without losing control. (demystifyingindustrialtech.com)

We still fear decisions, even when no one remembers why. (demystifyingindustrialtech.com)

Sources & further reading

Dark Ages (Finstere Zeiten) is a German short film (2002), length listed as 12 minutes by FBW. (fbw-filmbewertung.com) - German

Work aids - Dark Ages (Finstere Zeiten). (materialserver.filmwerk.de) - German

ZEIT/dpa report on Gerd Knebel’s death (Jan 25, 2026). (DIE ZEIT) - German

Amazon’s 2016 shareholder letter (one-way vs. two-way door decisions; decision velocity). (Amazon News) - English

Premortem method (Gary Klein, HBR, 2007). (hbr.org) - English

The carpenter and his apprentice are played by Badesalz, a cult-famous comedy act from the German state of Hesse. For readers outside Germany: Badesalz (literally “bath salts”) was a comedy duo founded in the early 1980s by Henni Nachtsheim and Gerd Knebel.

A sad update, since this matters for how we talk about them: Gerd Knebel died on January 24, 2026, at age 72, as reported by multiple German outlets citing dpa and statements from his long-time partner Henni Nachtsheim.