When your best tool becomes your worst habit

How familiar solutions reshape problems and limit judgment

Most leadership failures don’t begin with bad intentions or poor intelligence.

They begin with competence applied too automatically.

The “golden hammer” mindset describes what happens when a leader relies on an approach that has worked well before and keeps applying it, even as the nature of the problem changes. Abraham Maslow captured this tendency decades ago: when one tool dominates, everything starts to look like a nail.

This is not a flaw of weak leaders.

It is a predictable outcome of experience in positions of responsibility.

And that is exactly why it limits leadership.

This is not an argument against experience or decisive action, but for treating problem framing as a core leadership responsibility rather than a side effect.

Why this is more than a personal blind spot

Leadership is not primarily about solutions.

It is about problem framing.

Long before a decision is made, a leader has already answered a quieter, more consequential question:

What kind of situation am I in?

The golden hammer bypasses this step.

It replaces diagnosis with recognition: “I know this pattern.”

In stable environments, this works.

In changing environments, it quietly breaks judgment.

The danger is not choosing the wrong action.

The danger is never realizing that the problem itself was misunderstood.

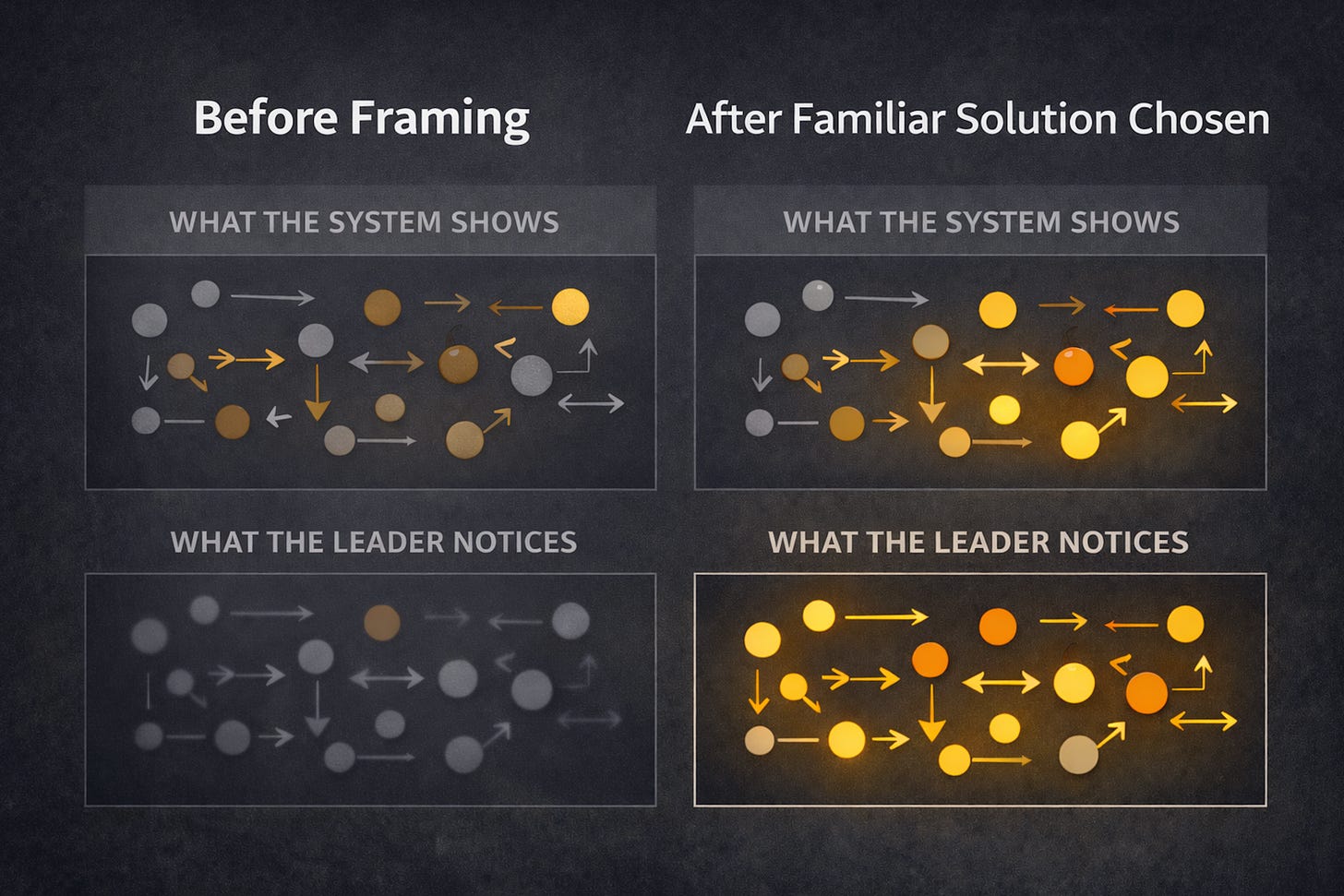

What the Golden Hammer really changes

The golden hammer doesn’t just affect what leaders do.

It affects what they notice.

Over time, leaders begin to:

privilege information that fits familiar explanations

discount signals that don’t align with past success

treat disagreement as resistance rather than insight

This is not willful ignorance. It is cognitive efficiency under pressure.

Research on decision-making shows that people responsible for outcomes favor coherent stories over incomplete ones. A clean narrative enables action. A messy reality delays it.

The golden hammer provides coherence.

But coherence is not the same as accuracy.

A concrete example (without hero myths)

Consider restructuring.

Reorganizations are legitimate tools. They can reduce friction, clarify responsibility and align incentives.

They are also attractive because they:

are visible

signal authority

create the feeling of control

When results deteriorate, restructuring offers a simple explanation: “The structure was wrong.”

Yet many performance problems are not structural at their core. They arise from:

unresolved trade-offs

unclear decision ownership

overload rather than misalignment

erosion of focus or trust

A structural change cannot solve these issues on its own.

But the golden hammer makes it feel as though it can.

Movement replaces understanding.

The real leadership cost (often missed)

The deepest cost of the golden hammer is not failure.

It is premature closure.

Once a familiar solution is assumed:

inquiry stops

alternative interpretations disappear

learning gives way to execution

Leadership shifts from sense-making to enforcement.

This is why experienced leaders sometimes struggle most in new contexts, not because they lack skill, but because their strongest skills narrow the field of vision.

How the Golden Hammer feels before it becomes visible

The golden hammer rarely announces itself as a mistake.

It usually shows up as relief.

There is a moment in many leadership discussions when tension drops too quickly. Agreement comes fast. The room feels aligned. Someone says, “This is clear,” and everyone nods. That moment often feels like progress.

In reality, it can be a warning sign.

Common early signals include:

impatience with further questions

irritation when alternative explanations are raised

a strong urge to “move on”

the quiet thought: “We’ve seen this before.”

None of these are wrong on their own.

But together, they often indicate that a familiar solution is being accepted before the problem has been fully understood.

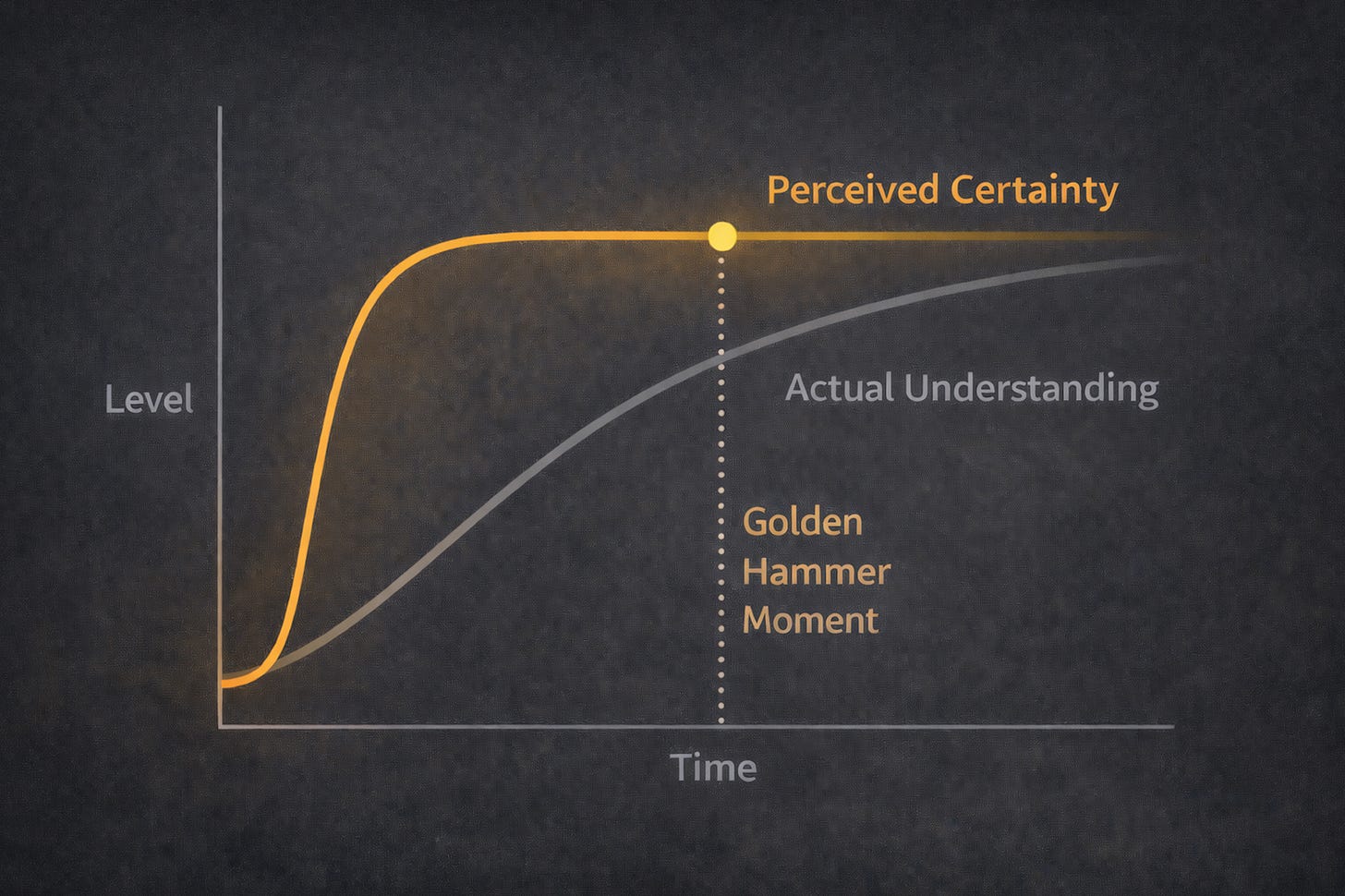

The exact point where judgment slips

The golden hammer takes over at a very specific point:

When a solution creates emotional certainty before cognitive clarity exists.

At that point, the solution doesn’t just address the problem, it defines it.

From there on, evidence is filtered, discussion narrows and momentum replaces inquiry.

This is why the effect is so hard to catch.

It doesn’t feel like poor leadership. It feels like decisiveness.

When the Hammer is the right tool

This matters: the golden hammer is not always wrong.

In truly stable, well-understood situations:

repetition creates reliability

standard responses reduce noise

speed matters more than learning

Organizations depend on this.

The problem begins when leaders fail to notice that the context has changed, while the organization continues to reward decisiveness, confidence and fast answers.

At that point, the golden hammer is no longer an individual bias. It becomes an organizational habit.

Experience vs. judgment

Experience is accumulated pattern recognition.

Judgment is knowing when patterns no longer apply.

The two are related, but not identical.

Good leadership requires holding them apart:

using experience as input

not allowing it to dictate the diagnosis

That separation is uncomfortable. It delays certainty.

But without it, experience turns into constraint.

What high-quality leadership looks like instead

Strong leaders do not abandon action.

They delay commitment, not movement.

They do three things consistently:

They invest time in framing before fixing.

Not endlessly, but deliberately.They allow competing explanations to coexist longer than feels efficient.

Because false clarity is more dangerous than temporary ambiguity.They scale the size of their actions to the quality of their understanding.

Big moves follow insight, not instinct.

This is not theory.

It is how leaders avoid locking organizations into the wrong path while still moving forward.

A common but costly misunderstanding

Leadership is often described as the ability to “have answers.”

In reality, leadership is the ability to know:

when answers are reliable

and when they are merely familiar

The golden hammer removes doubt.

Good leadership tolerates doubt long enough to learn.

A simple personal test

Before committing to a familiar response, experienced leaders can ask themselves one quiet question:

“Would this solution still make sense if this problem didn’t already have a familiar name?”

If the answer is unclear, the pause is doing its job.

This question does not block action.

It simply creates enough space for judgment to catch up with experience.

Getting started (without tools or frameworks)

This does not require new language or models.

Three disciplined behaviors are enough:

Name your default move.

Every experienced leader has one. Acknowledge it openly.Ask what would make that move inappropriate.

If no one can answer, the discussion is already constrained.Separate urgency from solution.

Pressure may demand action. It rarely demands this specific action.

These habits do not slow leadership down.

They prevent momentum from replacing judgment.

Final thoughts

The golden hammer mindset persists because it feels responsible, decisive and efficient.

But leadership is not about applying strength.

It is about applying the right kind of strength to the situation at hand.

Sometimes the familiar tool is exactly right.

Other times, the most capable leaders pause, not because they are unsure, but because they understand that authority without diagnosis is just force.

That pause is not hesitation.

It is the discipline that turns experience into wisdom.

Further Reading

Abraham Maslow: The psychology of science: a reconnaissance

Gary A. Klein: Sources of Power: How People Make Decisions

Donald A. Schon: The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think In Action

Daniel Kahneman: Thinking, Fast and Slow

Karl E. Weick: Sensemaking in Organizations

You've raised a very interesting point! I completely agree with what you're saying. I particularly like your statement that sometimes it's right and sometimes it's wrong to pull out the golden hammer. It's often used because it speeds up the process. Sometimes that can ensure survival, but most off the times it's smarter to invest the time. Similarly, it's important for the boss to demonstrate their competence from time to time—just not always and at every opportunity. As always, the dose makes the poison—and in this case, it's a very potent poison, so only homeopathic doses are advisable.

This nails something I've seen play out repeatedly in ops environments. The distinction between experience as pattern recognition versus judgment as knowning when patterns don't apply is brillant. I think the restructuring example is especially good because it's so visible and feels decisive, but often it's just moving boxes around instead of solving the underlying issue. The question about whether a solution would make sense if the problem didn't already have a familiar name is a keeper.